In 2010, 16-year-old Indie Landrum ran away from an unstable home where he lived with his mom and his grandmother. His older sister ran away when she was 16, and both of his brothers were incarcerated. Indie sought emergency housing at the San Diego Youth Services (SDYS) Storefront shelter, and lived there for several months before going into a long-term group home.

During his time at Storefront, SDYS began a dramatic transformation: the process of becoming a trauma-informed organization. Basically, that means instead of a staff member angrily asking a youth who’s acting out, “What’s wrong with you?” and punishing the behavior, staff members ask, “What happened to you?” and work with the kid on healing and recovery.

The results? Significant. Youth who were less likely to use the services now do, and more often. Police involvement and foster home/group home placements are down. And SDYS staff turnover has dropped. When Indie first arrived, “there were very specific rules that had to be followed to stay in shelter. If you weren’t in by 7:30 p.m., you couldn’t stay the night,” says Indie. “It’s not that they didn’t care, it just didn’t matter why you weren’t there.”

At that time, SDYS shelter staff worked with youth on a system of rules and rewards: You made your bed, you got a point. It’s the way most youth shelters across the U.S. work. If a kid loses a certain number of points, the kid gets put on a seven-day restriction phase. It’s modeled after how parents discipline kids when they mess up at home -- no phone, no TV, no video games. Kids are still required to go to dinner, group meetings, and shower, but they have to spend their hour and a half of free time in bed. If the kid continues to lose points while on restriction, they are asked to leave the shelter. Lose points on the first day of restriction? Out for the remaining six days and nights.

“The belief was that when kids have to fend for themselves outside of shelter it makes them appreciate being in shelter to the point that they change their behavior,” says Michelle Atkins, Storefront Shelter program manager from 2007 to 2011. It was a belief that was challenged by Gabriella Grant, director of the California Center of Excellence for Trauma-Informed Care, in 2009. After attending Grant’s workshop, Atkins and her team reviewed the files of hundreds of youth who had been on restriction over a three-year period.

“We could prove it wasn’t working,” says Atkins. In fact, they found the policy had a success rate of zero. It was effective for no kids. “Kids were most often asked to leave because they didn’t have the daily living skills or behavior management required to stay in shelter, and the restriction phase didn’t help with either,” says Atkins.

The question became: How can we make more effective policies? Instead of going straight to consequences, staff members started talking with kids who were breaking the rules about why they were having problems doing so. If a youth coming off the streets wasn’t oriented to daily living skills -- personal hygiene, making a bed, doing a chore, being on time, being respectful -- a staff member volunteered to model the skill and do it with the youth. To keep shaming, blaming, and ostracizing the youth to a minimum, staff members sat down with the youth at a time when no other youth were present.

And so SDYS joined a nascent and emerging nationwide movement of elementary schools, high schools, and juvenile courts that are jettisoning punitive discipline policies and adopting trauma-informed, resilience-building, and restorative approaches to care. What exactly does that mean?

Becoming trauma-informed is an evolutionary learning process, not a quick fix. There are no band aids in a trauma-informed toolbox. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAHMSA), a trauma-informed approach refers to how a program, agency, organization, or community thinks about and responds to those who have experienced or may be at risk for experiencing trauma; it is a change in organizational culture.

In this approach, the whole organization understands the prevalence and impact of trauma, the role trauma plays in people’s lives, and the complex and varied paths for healing and recovery. It is designed to avoid re-traumatizing already traumatized people, with a focus on safety first, including emotional safety, and a commitment to do no harm. It requires meaningful involvement of community members and trauma survivors in service and program planning, and close collaborations between public and private sector service systems.

Prior to 2010, SDYS had implemented a few trauma-specific services haphazardly. They needed something that involved everyone. After researching their options, they decided that becoming a trauma-informed organization was the best approach. “We knew we would not just get a certificate in trauma-informed care,” says Steven Jella, SDYS associate executive director. “Becoming trauma-informed would have to remain an ongoing issue of agency-wide culture change.”

Everything and everybody -- maintenance staff, budgets and contracts, board of directors -- would need to be included. Becoming trauma-informed is a paradigm shift, says Jella. “It’s not about a youth acting out, it’s about what triggered them.”

For Indie, it meant that when his grandmother died, he was allowed to skip group meetings, put sheets up around his bunk bed for added privacy, and stay up past lights-out to talk with staff about his grief, actions that otherwise would have racked up points, generated consequences, and ultimately run him the risk of getting kicked out of shelter.

As a queer youth in the process of coming out as transgender, Indie also benefited from the increased safety associated with trauma-informed care in a system where one-third of trans youth are turned away from shelters because of their gender identity. He met two other transgender youth while living at Storefront. Staff members referred to them by their requested identities and let them express themselves accordingly. As requested by the youth, bathrooms were made ambiguous, and they were given the opportunity to decide which side of the room they felt most comfortable sleeping on, male or female.

“I got honor role for the first time in my life when I lived at Storefront,” says Indie. “It felt like the staff at Storefront actually cared. I still seek support from staff because the connections are so strong.”

Becoming truly trauma-informed takes time, involves everyone The process of becoming a trauma-informed agency was no small undertaking. The 220 staff members of SDYS, a non-profit charitable organization founded in 1970, serve about 13,000 youth and families every year through about 25 programs in 14 locations around San Diego County. The agency prevents delinquency and school failure, reduces homelessness, promotes mental health and addiction recovery, and breaks the cycle of child abuse and neglect.

Young people – from newborns to 25-year-olds -- and their parents or caregivers are referred to SDYS from San Diego County’s Child Welfare Services, Probation Department, Police Department, schools, other non-profit agencies, and from the streets.

“Our population has high rates of trauma,” says Stephen Carroll, director of the SDYS Homeless/Transition Age Services Division that includes the Storefront youth shelter. “We wanted to make sure this effort impacted the whole agency.”

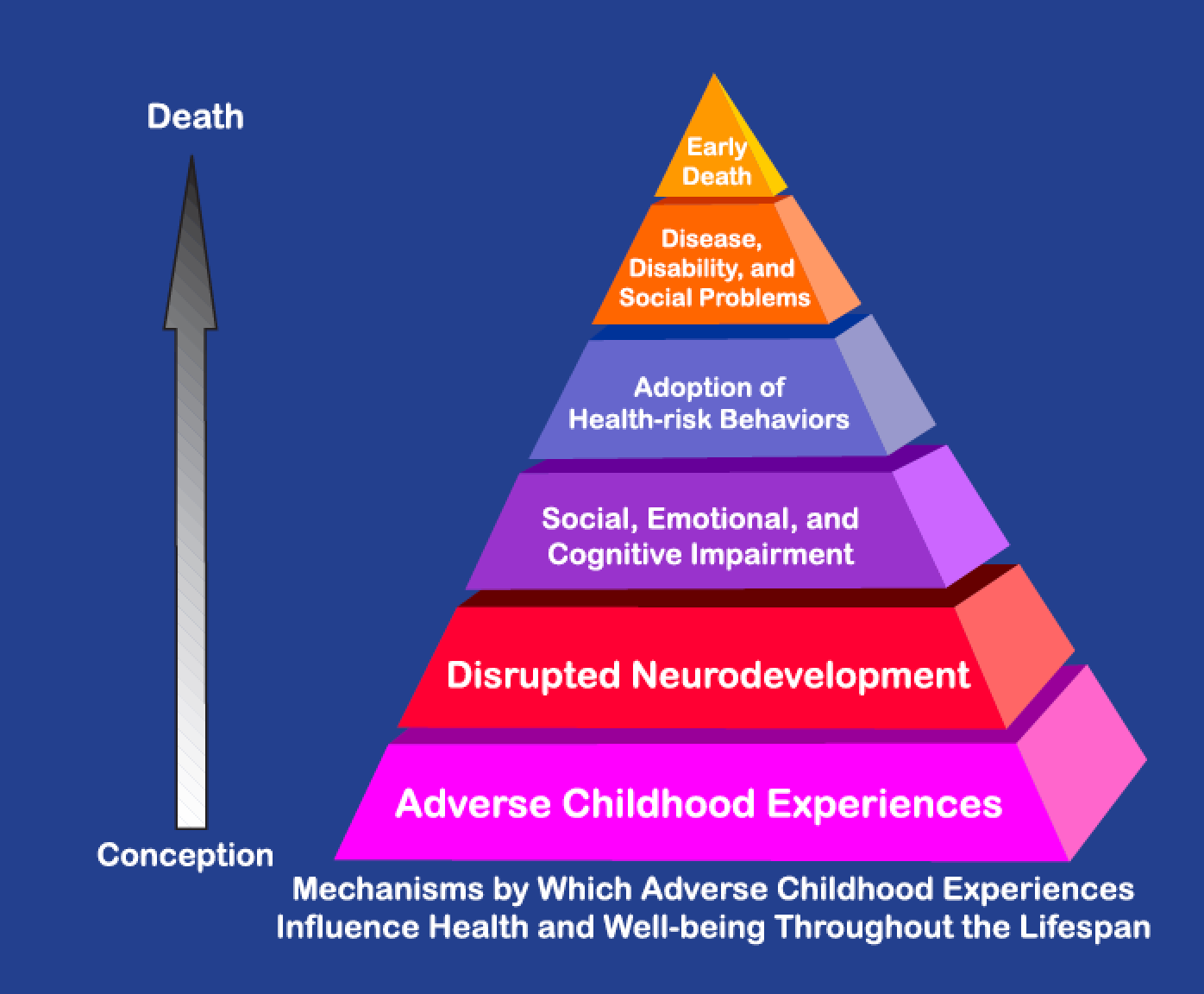

Without intervention, high rates of trauma can result in adult onset of chronic disease, mental illness, violence and being a victim of violence, according to the CDC’s Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study). The study measured 10 types of childhood trauma: sexual, physical and verbal abuse, and physical and emotional neglect; and five types of family dysfunction – witnessing a mother being abused, a household member who’s alcoholic or drug dependent, who’s been imprisoned, or diagnosed with mental illness, or loss of a parent through separation, divorce or other reason. Of course there are other types of trauma, such as bullying and community violence, but the ACE Study measured only 10.

Each type of trauma was given an ACE score of 1. Think of an ACE score as a cholesterol score for childhood trauma. A person who has been sexually abused and physically neglected, and grew up with an alcoholic mom and an incarcerated dad would have an ACE score of 4.

The study found that of the 17,000 mostly white, middle class, college educated, Kaiser-insured adults, two-thirds experienced at least one type of severe childhood trauma. Most had suffered two or more.

The study found that a person with four or more adverse childhood experiences is 12 times more likely to attempt suicide, 10 times more likely to use injection drugs, seven times more likely to be an alcoholic, two-and-a-half times more likely to have a stroke, and twice as likely to have cancer. A person with an ACE score of 6 or more has a shorter life expectancy – by 20 years.

ACE studies have now been done in 28 states and Washington, D.C., with similar results. And what about youth at risk or experiencing homelessness? Well, if you consider youth behind bars “at risk,” a recent study conducted by Florida State’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and the University of Florida found that 50 percent of the 64,000 incarcerated youth surveyed experienced 4 or more ACEs, compared to only 13 percent of the original CDC ACE Study.

From May to November 2011, SDYS took three critical steps to become trauma-informed: — The associate executive director sent an email to all agency staff explaining the interest in making a shift to trauma-informed care. Included was a document adapted from the Hollywood Homeless Youth Partnership (10 reasons for Integrating Trauma-Informed Approaches in Programs for Runaway and Homeless Youth).

To encourage the staff to ask, “What does this have to do with what I do?,” all staff members were asked to rewrite their job descriptions to include trauma-informed care language. “This brought up questions,” says Carroll. “For example, housing and facilities staff asked: ‘Why are you asking us to be trauma-informed? We repair broken sinks.’

They had to figure out how being trauma-informed impacted them.”

--- They formed their own trauma-informed work group and applied to join a national learning community sponsored by the National Council for Behavioral Health and supported by SAMHSA. “That was the catalyst for us adopting trauma-informed care as a culture across our entire agency,” says Carroll. The SDYS trauma-informed care work group – comprising the associate executive director, three division directors and the program manager for the family/youth support partners program -- joined 20 other organizations from across the country that were also becoming trauma-informed.

“Some were taking on trauma-informed care for the first time,” recalls Carroll. “Some agencies had already gotten the ball rolling. We learned from one another. The other 20 organizations and staff supported us as we mapped out a plan forward, and we supported them.”

-- The SDYS work group decided to focus on developing their workforce. “If this was going to be the culture of the agency, we needed to train everybody at all levels,” says Carroll.

They developed three trainings: Trauma-Informed 101 Philosophy, Trauma-Informed 201 Care and Practice, and Trauma-Informed Care for Supervisors. To date, 355 people have participated in the Trauma-Informed 101 Philosophy, 98 people in Trauma-Informed 201 Care and Practice, and 50 in Trauma-Informed Care for Supervisors. Training participants have included SDYS staff, volunteers, foster parents, and outside agency staff. Training has been facilitated in partnership with Gabriella Grant of the California Center of Excellence for Trauma-Informed Care. Even the agency’s board of directors requested training.

“They were really receptive,” says Carroll. “They felt like it would make a difference.”

The four-part Trauma-Informed Care for Supervisors training was critical, says Carroll. This makes the organization itself trauma-informed, since the staff interact with each other using trauma-informed approaches. Having this knowledge enables supervisors to respond to staff with care and understanding, instead of using a 100-page rulebook.

“That's the most important part,” he says. “A lot of agencies provide trauma-informed training to their staff, and say ‘We’re trauma-informed’. You can say it, but you won’t necessarily provide lasting change within the organization. You can't offer it once and expect an agency to stay on that path.”

To provide lasting change, they tackled trauma-informed care sustainability through three approaches:

-- Participation in an external online national community of practice, a listserv managed by the National Council for Behavioral Health. Its members ask and answer questions, facilitate webinars, and share links to articles, conferences, speakers, resources, and trainers.

-- Participation in a local in-person community of practice, the San Diego -Trauma-Informed Guide Team. The guide team was established in 2008 in response to another workshop led by Grant. Today, more than 160 agencies participate in the team. Members pick each other’s brains, assist their agencies in making the shift to trauma-informed practices, and cheerlead each other to keep up the momentum.

-- Participation in an internal community of practice -- the SDYS trauma-informed work group. During monthly meetings, 20 trauma-informed care champions from across all programs review and advance the agency-wide cultural shift. In-person meetings are complimented by an agency-wide intranet that houses an online resource library for all staff.

The response from staff? “The overwhelmingly majority of staff support it,” says Carroll. “Instead of relying on black-and-white rules, the staff have to go to where clients are and work with them,” he says. “The staff like the fact that it’s challenging, and it gets results. They feel better that the care is individualized and they get to be creative. There’s still a feeling of uncertainty. When they don't have black-and-white rules and protocols, they question: Are we doing the right thing? Should we have intervened sooner? Later? It's all good -- it’s part of self-reflection and critical thinking.”

Although most of the staff embraced the changes in the agency, a few people left. That’s to be expected, says Carroll. Those who left said a trauma-informed approach meant the agency was becoming “too soft” on the youth, allowing them to “get away with murder”, to break too many rules. “Some of the resistance might be that they haven't completed their own healing process,” says Carroll.

Last year, in a Trauma-Informed 101 staff training, participants anonymously completed the 10-question ACE survey. In nine of 10 questions, staff members, volunteers, and foster parents who attended the training ranked higher than the original CDC ACE Study participants. The information was incorporated into the supervisors training to build understanding of the “wounded healers” concept.

SDYS recognized early on that service providers are triggered the same ways youth are -- by their traumatic histories. As a result, these “wounded healers” also needed ongoing training and supervision with a big focus on staff wellness, health, and prevention. “Part of being trauma-informed is acknowledging that the staff have a history of trauma, too. That's why we have the supervisor training. They can receive the support of their supervisors,” says Carroll.

Revising, improving, updating…. the process never stops.

Over the last year, the SDYS trauma-informed care work group has revised its trauma trainings, updated policies and procedures for youth and family involvement, and are in the process of developing a worksite wellness program based on a survey of 117 staff to be used as a foundation for a combination of in-house and community-based resources.

The agency adopted Seeking Safety as their trauma-specific treatment, in combination with EMDR, Motivational Interviewing, and expressive arts therapies. The shelters have incorporated contributions from youth into their quality improvement procedures through “lots and lots of tools -- suggestion boxes, meetings, written, verbal -- enough space for everyone to have the input to meet their needs,” says Atkins.

A new project, the Transition Age Youth (TAY) Academy -- a partnership between SDYS, the YMCA, South Bay Community Services, Harmonium Inc. and Nash & Associates -- was recently designed from the ground up as a trauma-informed, resilience-building program. It operates out of four drop-in resource centers across San Diego County. The program provides resources and support to young adults ages 14-25. Anyone is welcome -- not just homeless, foster, or substance-dependent youth.

Youth, community, county, and social service providers helped design the program. The program employs youth who have experienced trauma and who are vital in making connections with other young adults, and connection coaches that work with youth to create vision plans – a road map for their futures.

“TAY Academy staff members aren’t called case managers,” says Carroll, “because youth emphasized that they weren’t cases and they don’t want to be managed.”

The program has no formal referral process. TAY have the choice of when to walk in and when to exit. This avoids youth being “passed” from adults at one agency to another. “From a trauma-informed lens, it avoids re-traumatization,” says Carroll.

Over the course of the last year, 1,030 youth made over 12,000 visits to the program, with the average youth making about 12 total visits. The program considers these numbers to be significant outcomes, considering the lack of trust and low utilization rates associated with the TAY population.

How else does SDYS measure the impact of trauma-informed care? It’s tricky. The purpose of trauma-informed care is culture change -- to weave and braid it into everything -- so it doesn’t simply become the next flavor of the month. Unfortunately this can make it expensive and time-consuming to measure, because programs must first ascertain that the changes they're seeing can be attributed to trauma-informed practices, rather than some other outside factors.

“We looked at serious incident reports -- police involvement, foster home/group home placements -- ultimately the end result of not addressing triggers early on,” says Jella.

Based on a preliminary look at these indicators, they found significant drops in the overall number of reports from the past three to five years as well as the severity of reports from the past one to two years. “Something has shifted,” says Jella.

Prior to adopting trauma-informed care, there was a 40% staff turnover rate at SDYS, not uncommon for nonprofits. After agency wide inclusion of trauma-informed principals and policies it dropped to 33%, a significant decrease.

“Staff typically stay longer in jobs where they get support and training and feel competent by seeing results. If they see results they feel better and they intervene better with the kiddos. That’s our rationale, anyway,” says Jella.

Indie, who is now 21 years old, works as a community organizer on an alcohol and drug prevention program that focuses on reducing LGBTQ youth’s access to drugs and alcohol. Indie wants to keep working with youth, get a masters degree in social work, and maybe pursue a doctorate degree.

Before living at Storefront, Indie never envisioned living past age 18. “When I was there it gave me a reason to keep going,” says Indie. “I never knew anybody that came from an intense background and was doing good things. Everyone I knew was doing drugs, in jail, or working night shifts at a Wal-Mart. It’s really important to see people doing good things. Now I know I can make a difference.”

Comments (0)